Tutorial

This tutorial assumes no prior understanding of object pooling, and will introduce the concept bit by bit. The aim is to gradually build up knowledge about object pooling in general, when to use pooling, and how to pool objects with Stormpot specifically.

What is an Object Pool?

An object pool is a homogeneous collection of objects. Whenever one such object is needed for something, it is taken from the pool instead of being allocated anew. Once an object has served its purpose, it returns to the pool so that it can later be reused. We say the collection of pooled objects is homogeneous, because it does not matter which of the objects are picked to be used in a given case. This is where pools differs from caches: in a cache, the objects are distinct, and have some identity by which they are looked up when needed. In a pool, there is nothing to look up by, and any object will do.

The purpose of the pool, is to prevent as many allocations of the pooled objects as possible, with as little overhead as possible. If the objects being pooled represent a limited resource, a secondary purpose of the pool is to enforce an upper bound on the number of these objects that are in use, at any given time.

When a pool represents a limited resource, then it is often shared among multiple threads. An example of this could be a database connection pool in a typical Java web application. Such pool implementations obviously need to be thread-safe, and Stormpot fits this bill. In Stormpot, there is always an upper bound on how many pooled object instances there can exist at any one time, and the Stormpot pool implementations are indeed thread-safe.

When Should I use an Object Pool?

Java is a garbage collected language. Objects are allocated on a shared heap of memory. The garbage collector provides the illusion of infinite memory, by periodically removing unused objects from the heap. This is the most efficient way to allocate and free memory.

Most object allocations in Java are done by bumping a pointer into a thread-local allocation buffer. This common fast-path allocation is typically just 10 native instructions. Once the memory has been allocated, the object has to be initialised with the object initialiser, and constructed with the constructor.

Freeing memory is done in batches, called collections, following the allocation rate and the demand for new memory. The garbage collector traces through the object graph, finding all the objects that are live and in use. All the objects that are not live, are garbage and can be collected. This often means that the threads of the application, the mutator threads, needs to be paused so the collector can get a consistent view of what is live and what is not. These pauses are a necessary evil of a garbage collector. The pause times scale with the number of live objects, not the size of the heap, so high object retention has a bigger performance impact than a high allocation rate.

An object pool cannot beat the garbage collector on throughput and latency of memory allocation and freeing, because the pool will necessarily have to do some form of synchronisation to coordinate access to its limited set of objects. In other words, if objects are pooled for performance reasons, the cost of the object initialisation and construction must outweigh the overhead of the pool. This leaves us with only two good cases for object pooling:

-

Objects that have very expensive initialisation or construction.

-

Objects that represent a limited resource, such as network connections or threads.

Java already does thread pooling with the Executors framework, so this use case is solved.

This leaves network connections — for instance to a database, or some other kind of remote service — as the archetypical example of something you want to pool.

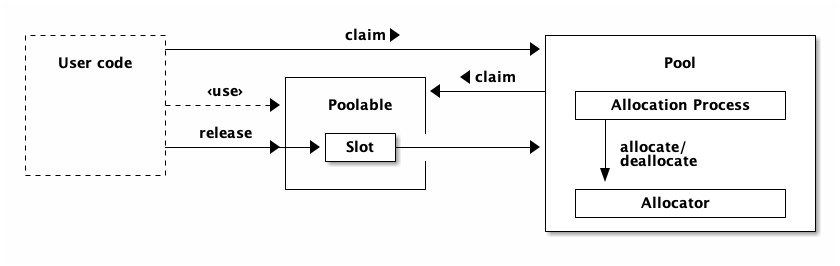

The Elements of an Object Pool

There are three central elements to a pool, and a number of peripheral elements. The central elements are the following:

-

The objects being pooled. In Stormpot terms, these are a subtype of

Poolable, and their number per pool is determined by the configured size of the given pool. The implementation of thePoolableinterface is supplied by the user code, through theAllocator. -

The

Allocatorcreates and destroys the objects being pooled, with theallocateanddeallocatemethods, respectively. There is one allocator per pool, and it is supplied to the pool through the pool configuration, typically via thePool.frommethod. -

The pool itself, which is an implementation of the

PoolAPI. Implementations of this API is supplied by the Stormpot library.

The pool lets interested parties claim objects as needed, and expects them to be returned via a call to the release method on the Poolable interface.

The release method on the poolable works by delegating to a Slot object that was given to the poolable, through the allocator, when the poolable was created.

It is the job of the pool to turn as many calls to claim and release into as few calls to allocate and deallocate as possible.

The pool has to do this with the smallest overhead possible, and while observing the configured upper bound on the number of objects.

This upper bound is called the size of the pool.

When all the objects in the pool are claimed, the pool is said to be depleted.

If you call claim on a depleted pool, the call will block until at least one object is released back to the pool.

More than one thread at a time can be blocked trying to claim objects from the pool.

The claim call does not guarantee fairness, so there is no way to know before hand, which of the threads will be unblocked when an object is released.

The pool has an allocation process to allocating and deallocating the poolable objects, because these are presumably expensive operations. The allocation process is by default implemented as a dedicated background thread. This way, the threads that come to the pool to claim objects, don’t have to pay the cost of allocating those objects. This reduces the latency for claim in the general case.

In essence, the central parts of the pool fit together like this:

Object Pooling in Practice

Let’s take what we learned in the previous section, and put it into practice. It is clear from the diagram and the explanation, that we need to do two things for the type of the objects we want to pool:

-

They have to implement the

Poolableinterface. -

They need a field for the

Slotobject with which they will inform the pool when they are released.

The simplest possible implementation of this looks like this:

// MyPoolable.java - minimum Poolable implementation

import stormpot.BasePoolable;

import stormpot.Slot;

public class MyPoolable extends BasePoolable {

public MyPoolable(Slot slot) {

super(slot);

}

}The implementation of the Poolable interface is largely left to the BasePoolable class.

Objects of this class don’t really do much, other than correctly implementing the Poolable interface.

However, it is a skeleton to which we can add the functionality and the expensive resources that are the reason we are pooling these objects in the first place.

Next, the pool can’t create instances of this class by itself.

It needs the help of an Allocator implementation to do that.

The allocation of these objects will by default be happening in a dedicated allocation thread, such that this thread pays the cost of the presumably expensive allocation.

Therefor, it is generally a good idea to do as much work as possible during the allocation, such that it is as cheap as possible to claim and use the objects.

There is one moderation to this rule, however, because the pool only has one allocation thread.

The more expensive objects are to create, the longer it will take to fill the pool.

Likewise, if the objects expire and churn with a high rate, the allocation thread might not be able to keep up with the demand for reallocations.

The above describes the default threaded allocation mode. The pool can also be created in other modes where the objects are either all allocated up front, or inline with the claim calls. See the configuration page for descriptions of the different allocation modes.

Here is what an Allocator that allocates the above objects, can look like:

// MyAllocator.java - minimum Allocator implementation

import stormpot.Allocator;

import stormpot.Slot;

public class MyAllocator implements Allocator<MyPoolable> {

public MyPoolable allocate(Slot slot) throws Exception {

return new MyPoolable(slot);

}

public void deallocate(MyPoolable poolable) throws Exception {

// Nothing to do here

// But it's a perfect place to close sockets, files, etc.

}

}There’s not much to it.

The allocate method gets the Slot instance that the specific Poolable has to use, for informing the pool when it is released.

If the allocate method throws an exception, or returns null, the allocation is considered a failure.

Failed allocations may bubble out of claim calls, as the cause of a PoolException.

They might also not bubble out, because the pool keeps track of how many allocations have failed, and will automatically retry the allocations until they succeed.

If that happens, the exception is simply discarded.

This is called proactive reallocation.

Meanwhile, failed allocations still count towards the size of the pool, so there are only so many exceptions that the pool can contain at any given time.

This combination of bubbling exceptions out through claim, and proactive reallocation, means that the pool copes well with failure.

If there are periods where the allocator cannot create new objects – for instance if the objects need some kind of network connection, but the network has been disconnected – then the user code that calls claim will not wait for the entire duration of the timeout, to be notified of the failure condition, but instead immediately get an exception.

Then, when the failure condition is corrected – for instance if the network comes back up, to continue that example – then the proactive reallocation will begin replacing the failed allocations with good ones.

This way, the user code doesn’t have to go through a whole pool full of exceptions, to get a useful object.

Now, we have a type of object that we want to pool, and we have an Allocator implementation that can create them.

All that is left to do, is to configure and instantiate a pool, and put it to use.

Here’s a simple example of what this could look like:

Pool<MyPoolable> pool = Pool.from(new MyAllocator()).build();

Timeout timeout = new Timeout(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

MyPoolable object = pool.claim(timeout);

try {

// Do stuff with 'object'.

// Note that 'claim' will return 'null' if it times out!

} finally {

if (object != null) {

object.release();

}

}The Pool.from method takes the allocator and returns a PoolBuilder, that contains the given allocator and some default configurations.

The PoolBuilder can then be configured further if we so desire, or we can use it to create our Pool instance.

Once a pool object has been created, it is immediately ready for use, though the calls to claim might block until a sufficient number of objects has been created.

More Elements of Stormpot

When it comes to object pooling with Stormpot specifically, there is more to it than the three central elements of the pool, the poolable objects and the allocator. We have already seen the slot object, and how it is used to inform the pool when an object is released. And we have seen the dedicated allocator thread, that uses the allocator to keep the pool filled with objects. We have also seen hints at the life cycle of the pooled objects: first they are allocated, then they are claimed and released a number of times, and finally they are deallocated.

There are three reasons an object can get deallocated: the object expired, the pool was resized to be smaller, or the pool was shut down. These three situations are particular to how Stormpot works.

Object Expiration

Whether or not an object has expired is decided by the configured Expiration strategy on every call to the claim method.

If the claim method finds an object that has expired, then it is sent off to be deallocated, and another candidate object is tried.

The hasExpired method of the configured expiration is therefor very performance critical, as it may be called more than once for every call to the claim method.

You can implement and configure your own Expiration implementation if you want, but Stormpot also comes with a couple of implementations of its own.

The default expiration policy expires objects after they’ve been circulating for somewhere between 8 to 10 minutes.

This implementation chooses the expiration age randomly on a per object bases, and thereby avoids expiring all objects at the same time.

If something out of the ordinary happens, and an object expires while it is claimed (depending on what "expired" means for your use case), then the object can be explicitly expired with the expire method on the Slot.

The expire method must be called while the object is still claimed, and the expiration will not take effect until the object is released.

Once released, the explicitly expired object cannot be claimed again, and it will be deallocated.

The BasePoolable class re-exposes the expire method for convenience.

Pool Resizing

A pool is configured with an initial size, through the the size property of the PoolBuilder.

However, this size is not fixed.

The target size can be set and queried whenever desired, using the relevant methods on the Pool.

Changing the size on the PoolBuilder has no effect on pools that have already been constructed.

The setTargetSize method allows anyone with access to the pool instance, to grow or shrink the pool as they see fit.

This works by immediately setting the target pool size to the new value.

There is no way to tell when the pool will actually reach the new target size.

Once a new target size has been set, the pool will work towards the set goal at its own pace.

The reason is that when the pool is shrunk, it cannot force currently claimed objects to suddenly be released, so that they can be deallocated.

Likewise, it takes time to allocate the new objects when the pool is grown.

The pool is otherwise designed to never have more objects than its target size, allocated at any one point in time.

Obviously this isn’t so when the pool is in the process of shrinking towards a new smaller size.

The resizing process itself works by simply allocating more objects than are deallocated, when the pool is growing, or by deallocating more objects than are allocated, when the pool is shrinking.

Shutting the Pool Down

Calling the shutdown method on a Pool initiates the shutdown process, but does not wait for it to complete.

The pool is not fully shut down until all the objects in it have been deallocated.

This can take a while, since objects that are claimed and in use cannot be deallocated until they are released back to the pool.

How long this takes depends entirely on the user code.

It also means that if an object has leaked – that is, it has been claimed and then forgotten, never to be released back to the pool – then the shut down process will never complete.

The shutdown method returns a Completion object, that allow you to await the completion of the shut down process.

The await method takes a Timeout object, so it doesn’t wait forever, and returns boolean true if the shut down process completed within the given timeout period.

This is the only way to tell whether or not the shut down process has completed.

Timeouts

All blocking operations in the Stormpot API take Timeout objects as arguments.

While timeout objects can represent very long timeouts, they cannot extend for an eternity.

This, at least in principle, prevents the blocking methods from waiting for forever.

The main blocking methods are the claim method on the Pool interface, and the await method on the Completion interface mentioned in the previous section.

Other blocking methods are implemented in terms of these two.

Timeout objects are immutable value objects, so they are fine to keep in static final fields and shared among multiple threads.

They also have unit independent equality semantics, so a timeout of 1 second is equal to a timeout of 1000 milliseconds.

Timeouts are also independent of variable calendar time, meaning that they don’t grow or shrink with passing leap seconds or daylight savings time adjustments.

The Timeout objects have a number of methods that expose the mechanics of how Stormpot uses the timeout objects, but you need not concern yourself with that, unless you want to use it in your own implementations of blocking operations.

Reallocator

Reallocator is an interface that extends the Allocator interface, and adds a reallocate method.

This method is a combination of deallocate and allocate, in that order, and has the opportunity for reusing the Poolable instances.

This can help reduce object churn and fragmentation in the old heap generation, thus helping to delay or prevent the full garbage collection pauses.

Reallocators can also be used to implement a more expensive expiration check. See the performance page on how to do that.

Configuring Stormpot

Stormpot is configured by setting properties of the PoolBuilder.

The PoolBuilder objects are mutable, and the setter methods return the same modified instance.

They are also Cloneable, so code that prefers to work on its own private instance can do so by calling clone.

Once a pool has been constructed with a particular configuration, it no longer needs the PoolBuilder.

A snapshot of the pool configuration is captured in the pool itself, and the PoolBuilder will no longer be consulted by that pool.

This allows you to modify and reuse the PoolBuilder for constructing other pool instances.

The Allocator instance is the only thing that must be configured, and this is enforced by the Pool.from method.

All the other configuration properties have somewhat reasonable default values.

Other properties that might be interesting to configure, include the pool size, and the Expiration instance.

See the configuration reference page for more information on how to configure Stormpot.

Alternative Pool Modes

Stormpot comes with two alternative pool modes: the inline pool mode and the direct pool mode.

The Inline Pool Mode

In the inline pool mode the objects are initially allocated when the pool is created, and then deallocated and reallocated as part of the claim calls.

This mode is enabled by creating the pool with the Pool.fromInline() method:

Pool<MyPoolable> pool = Pool.fromInline(allocator).build();

MyPoolable obj = pool.claim(TIMEOUT);

if (obj != null) {

System.out.println(obj);

obj.release();

}The inline mode is similar to the threaded mode in many aspects, but with the services provided by the background thread disabled. For instance, there is no background expiration checking, and no background reallocation of failed allocations.

Since the pool in the inline mode will deallocate and allocate objects as part of the claim calls, it is possible that it will take longer for the call to return than what is specified by the given timeout.

The Direct Pool Mode

In the direct pool mode the objects to be pooled are directly given to the pool upon construction, rather than being allocated and maintained in the background.

This mode is enabled by creating the pool with the Pool.of(…) method:

Object a = new Object();

Object b = new Object();

Object c = new Object();

Pool<Pooled<Object>> pool = Pool.of(a, b, c);

try (Pooled<Object> claim = pool.claim(TIMEOUT)) {

if (claim != null) {

System.out.println(claim.object);

}

}In this mode, all the given objects are immediately available to be claimed, instead of having to wait for a background thread to allocate them. The objects given are never expired, and never deallocated. Explicitly expired objects are simply returned to the pool. Precise leak detection is also turned off.

This means that no background thread is started for pools created in this mode, which makes them much more light weight. This makes mode good for temporary and short-lived pools, or for when the objects are effectively immortal and can be allocated up-front.

One drawback of this mode, is that the pool cannot be resized.

The size of these pools are fixed, and given by the number of objects passed to the Pool.of(…) method.

If you need to be able to resize the pool, then you should take a look at the inline pool mode instead.